When you’re wine shopping in a store, you’ll usually see “shelf talkers,” those little tags that shout out wine ratings and accolades below the bottles, practically begging you to buy a bottle…or a case. If not, you can just check reviews online from, say, Wine Spectator, or even snap a photo of the label using your Vivino app and get notes from thousands of previous customers. You’ll typically find out what grapes were used, where they were grown, and other highlights. But for many, it’s important that the dissertation includes “oakiness,” how its aroma, taste, and texture is influenced by putting that newly-fermented grape juice into oak barrels for anywhere from several weeks to several years.

Not so long ago, vintners fermented and transported wine in oak barrels and even larger containers, though that’s largely changed on account of the cost of barrels, and their relatively modest size, typically 225 liters or about 59 gallons–the standard Bordeaux size. Contrast that with closed- or open-top stainless-steel fermenters, which often hold anywhere from 250 to 100,00 gallons. Famed Bordeaux winemaker Emile Peynaud began advoacting for their use in the 1960s, and they’re now the standard for both reds and whites, although clay and concrete “eggs” are also used. Unlike oak, stainless fermenters don’t impart any specific characteristics to the fermenting “must,” red-wine juice that includes stems, skins, and seeds, or free-fun juice for whites only. Many of these have built-in cooling jackets to control the pace of fermentation, leaving the business of aging and flavor-enhancing tasks to oak barrels.

Typically, barrels are made from three types of oak, based really just where these “Quercus” species trees grow: France; elsewhere in Europe; or America. French oak is the most expensive, and known for its subtle and nuanced influence, which aligns with a lot of French winemaking philosophy. American oak is the least expensive, but by no means cheap, and is also the most “assertive” in its influence, especially in the perception of sweetness it can create in what are very dry white wines. European oak, from countries including Croatia, Hungary, Romania, and Slovenia, is just slightly cheaper than French, and those barrels best supports wines intended to be more tannic and fuller bodied.

New wine often starts out in “new oak,” barrels never used before, and is then moved over time into barrels that have been used for one or several vintages. One of the great things about barrel aging, beyond adding flavors and aromas, is that it supports a slow, gradual, and measurable introduction of oxygen, which reduces astringency and enables processes like malolactic fermentation, which convert tart malic acid to “creamy” lactic (read: milk) acid.

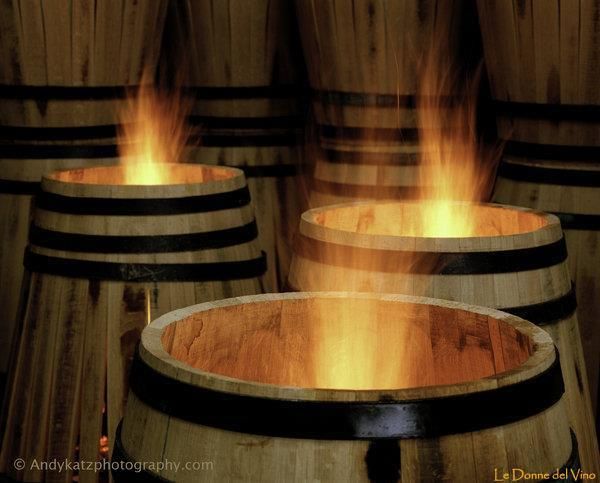

Barrels can also be changed depending on their type (French, European, or American) and their “level of toast,” the process of reusing them after scraping their insides, disassembling them and literally placing the staves over an open flame. Another technique for reconditioning is barrel blasting the insides of the stave with dry ice, which removes the typical accumulation of tartrates but not the toast.

The bottom line is that all modern winemaking is heavily influenced to use oak—financially, logistically, in time-to-market, but most of all in quality and consumer perceptions and preferences. The relatively high cost of new barrels determines many wineries’ choices for what they use, and for how long, depending on the style their customers have come to expect. Interestingly, a lot of barrels deemed no longer useful for wine end up in distilleries, used to age whisky, and vice-versa.

However, oak barrels are, at a basic level, expensive, inefficient, and have a short life during which they’re fully useful. After perhaps five years, retoasting no longer works and they become inert. And even when new, their outsides contribute no benefits. They can be stacked—you’ve seen them six to maybe ten high in large wineries—but that requires expensive rack systems. And a lot of work. Barrels do bring an attractive, traditional look to a winery warehouse or tasting room that reinforces the powerful cultural heritage and consumer appeal of the industry and the agriculture behind it, and these won’t disappear anytime soon. Still, industry and its economics are more challenging than ever, and some new alternatives to barrel are making inroads on a traditional landscape.

One is the Flexcube, a South African invention that owns the global patents for the polymers and wine-aging and storage vessel designs. It had a modest foothold in the US market until some management problems occurred, and when Covid19 hit in March of 2020, Flexcube withdrew from the US market. Nick Karavidas tells me that he was a Flexcube customer at the time, and in October 2021, after pulling and tasting wine he’d been maturing using oak staves in previous-generation Flexcubes as inexpensive alternatives to stainless storage tanks for his small export wine bottling project, he was astonished at the quality and results. He took over as the exclusive Western U.S. sales and distribution company for Flexcube Australia.

Flexcubes are plastic-free, so they eliminate worries about such flavors emerging in the finished wines. They allow oxygen to enter at three different rates, depending on the winemaker’s preference: low, (6 mg/liter/year); medium, (9 mg/liter/year); and high, (12 mg/liter/year). With a sloped floor for easy draining, they’re also pallet-jack friendly, and stackable to 4,000 liters, in 45% less space than Bordeaux barrels. And of course, they entirely eliminate the cost of barrels while still getting the full flavor enhancements of oak staves, being shown loaded here.

Now, I don’t know when, or if, they’ll replace oak barrels in a significant way, and they’ll never have the elegant look or cachet of oak. And to work, winemakers can’t use thinner or lower-quality staves, or those cut in ways that don’t provide equal exposure of wine to wood. But as an effective, cost-efficient aging and logistics technology in an enormously competitive industry that seems to have grown beyond its means in many cases, Flexcubes may provide advantages that some very smart winemakers won’t be able to refuse.